When one of my rear brake calipers started binding, I visited a garage in Sparta thinking I'd have to wait for a new one to arrive from the UK. The owner Niko’s upbeat response made me feel a bit daft. "Why? I can fix it!"

I’d previously considered having a go at refurbishing calipers myself, but I never imagined that a mechanic might offer to do it. It’s a much more fiddly job than simply replacing the whole caliper, and the cost of labour usually makes it unviable.

So while Niko worked and we shared the few words we could understand of each other’s languages, I reflected on the ways we value human skill in different parts of the world.

Investments of time

I had been led to Niko’s garage by a nearby mechanic who, instead of telling me to shove off because brakes weren’t his thing, hopped on his motorbike saying "Follow me" and spent his own time and petrol giving my custom to his neighbour. Niko and I hatched a plan, and when the refurb kit arrived with a new set of brake pads a couple of days later, I returned to find him ready to get started. There was then an alarming moment when my Land Rover and his two-post lift decided not to get along (neither party would have come off too well) but Niko soon had the vehicle jacked and the offending caliper on the bench.

When the piston turned out to be seized, he had a tool for the job – not the latest £1200 gizmo from a meaty tools catalogue, but a DIY contraption created from an old brake master cylinder with a big lever welded onto it. The idea was to build hydraulic pressure inside the caliper to pop the seized piston out. Genius, and it bloody worked. Moments later the piston emerged blinking into the light.

Niko has been doing stuff like this for decades, and he has the dodgy knee to prove it. He was a mechanic in Athens before moving to the Peloponnese in 2005, and he's worked out of this garage in Sparta specialising in brakes since 2012. (He traces two long lines around his knee where surgeons will soon perform some sort of grizzly magic. Then he’ll be unable to work for weeks.)

I asked him how many calipers he has rebuilt – a stupid question that invariably gets a pulled face in response. "Sometimes ten in a day, sometimes two." Even averaging only two, that's a lot of calipers.

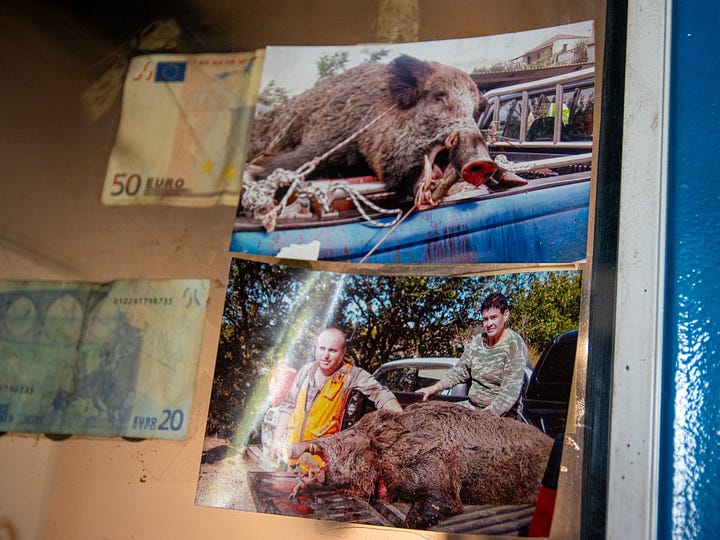

Outside was his Fiat Panda 4x4 that he’s owned for 25 years, using it for taking his four dogs into the mountains around Sparta on hunting trips. Nearby was his similarly aged Suzuki Samurai, whose engine and gearbox are in bits in his workshop. (I have very early memories of hammering between Scotland and England in one of those on a booster seat.)

The economics of it

Mechanics usually claim they only fit new parts rather than refurbish old ones for the sake of safety, and that's hard to argue with, especially with critical safety components like brakes. A garage doesn’t want your accident to have anything to do with them. (Nor do they want to be wrongly accused of causing an accident that had nothing to do with them.) As a mechanic, unless you’re totally confident in your workmanship, it’s just simpler to fit a new part, bill the customer accordingly, and chuck the old one in the bin. This is a bit like binning a door because it needs a new hinge, but it’s the norm.

The second kind of risk relates to the costs involved, and this is magnified where labour rates are high. Repair is usually more complex than replacement, so hiccups are more likely to emerge. (Something will be seized, a part will be missing or broken… there’s always something.) High labour rates cause the extra time spent dealing with these hiccups to have a major impact; the garage has to choose whether to swallow the extra cost or load it all onto the unimpressed customer, who may never return. Replacement is therefore preferred, as the outcome is more predictable, and there’s less risk of getting bogged down. Also, if you’re a main dealer, you’ll make a hefty markup selling the customer a new own-brand caliper anyway. (Elon Musk recently stated in an interview that car manufacturers make little profit selling new cars, relying more on the money they make selling over-priced parts to service the existing fleet. There are varying degrees to which this is true.)

So high labour rates disincentivise repairing things, but even so, Niko tells me that here in Greece most mechanics wouldn’t bother refurbishing a caliper. The risks are too high – unless you’ve been doing it for decades and you can put faith in your workmanship.

The dirty deed

So here’s what was done. (Skip this bit if mechanical stuff turns you off.)

Once the piston was popped out using Niko’s nifty contraption, the caliper was stripped of its piston and seals, then it spent half an hour in a couple of blast cabinets where Niko removed every trace of corrosion. He then dangled it on a wire where it received a coat of silver paint, and while that was drying, he returned to the Land Rover to strip and re-grease the calipers’ slider pins for both the rear wheels (these pins can also seize, along with the piston) and install a set of new pads. When the caliper was dry, the new piston was greased and popped inside, the new seals were set carefully into position, and then it merely remained to bolt the caliper to the vehicle and manually bleed the hydraulics.

"Like new!" Niko said with a cheerful smile. It looked it, and the brake now functions perfectly. Despite all this time and expertise and equipment, his labour only cost about €45 including tax. The refurb kit was about €10.

Should we lament the rarity of this kind of effort?

Social value and monetary value never perfectly align. Some work attracts less money than we’d like (eg. NHS nurses’ pay), and some work attracts more (eg. your boss’s pay). A free market should prevent the two from growing too far apart, but there will always be some disjunct. They are related, not paired.

It feels wrong to me that Niko’s skills and conscientiousness should be both uncommon and under-valued, but the more cash this kind of work commands, the less viable it becomes, compared with the less-skilled alternative work of replacing parts that could be repaired. Placing a higher value on the maintenance of old stuff accidentally makes new stuff more competitive. This helps drive the economics behind the increasing complexity and integration of our technologies, qualities which happen to also make skills like Niko’s feel more special and worth supporting. A strange, self-sustaining cycle.

Paying for the fuzzy feeling

Something feels instinctively right about having Niko do this work. I could have simply ordered a new caliper, left him alone to replace it and collected the keys when he was done. Instead, I have the satisfaction of commissioning a new lease of life for something original rather than throwing it in the bin and getting a replacement lump of new metal shipped across Europe.

It’s the motoring equivalent of growing your own electricity and running your chickens on solar power… or something. There’s a warm fuzzy feeling involved. It doesn’t mean we need to make a universal truth out of it, because sometimes the simple solution makes the best sense, and if we all ate electric chickens we wouldn’t have cool stuff and healthcare and whatnot.

Anyway, that’s enough overthink for today. I’m pleased to have supported Niko and his expertise. And I’m pleased to have the memory of photographing him at work.

Reminds me of the plastic bits around parts of the engine that prevent access. How many people now drive (myself included) with no real knowledge about how cars work?

Modern tech seems to be about distancing usage and the process that underlying it. For better or worse.